We have to double-check your registration and make sure this is not an automated entry in our system. Please complete the test below...

A Chinese famille verte dish with Johanneum mark, ex-coll. August the Strong, Kangxi

Dia.: 38 cm

Condition: (UV-checked)

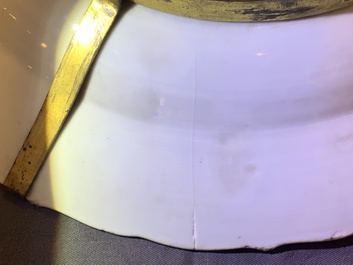

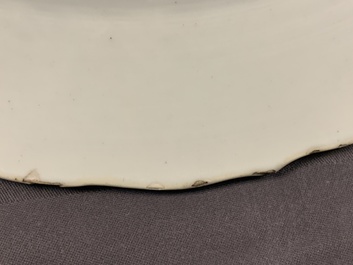

- The rim with various small superficial chips, glaze loss and burst glaze bubbles, as visible on the photos.

- A 3 cm glaze line located at ca. 5 o'clock, invisible on the backside.

- Between 5 and 6 o'clock a 9 cm hairline.

- Some areas with superficial wear to the enamel glaze.

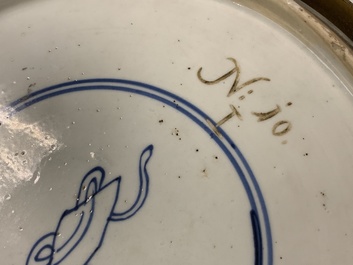

Provenance: With an engraved inventory number from the collection of August the Strong.

Saxon elector and Polish king Augustus the Strong was a major proponent of porcelain in the early 18th century. His love for the material drove him to imprison a talented young alchemist named Johann Friedrich Böttger in hopes of finding the formula for white porcelain, which at that time was a secret known only in China and Japan.

When Böttger perfected the recipe for porcelain in 1709, Augustus the Strong quickly founded the Meissen Porcelain Manufactory—the first porcelain manufactory in Europe—revolutionizing the porcelain market worldwide. He eventually amassed what is still the largest collection of Chinese and Japanese porcelain in the West, and began plans for a palace built to store the royal collection—an ambition that ultimately remained a dream.

The number of Chinese and Japanese porcelain Augustus the Strong collected grew to 29,000 until his death in 1733. Roughly 8000 pieces from his collection are still preserved in Dresden. They are actually the subject of a major cataloguing, digitization, and research project of the Dresden Porcelain Collection, something experts from all over the world are working on. The remaining third can be considered as a representative cross section of the original collection. The other pieces were dispersed throughout the world in many different ways: In the 19th century, when the Porcelain Collection tried to turn itself into a museum of world ceramics, so-called duplicates were sold or given away in exchanges. When Saxony became a republic in 1918, parts of the porcelain collection became public whereas others stayed with the royal family and were partly auctioned. More losses occurred during the Second World War, when the collections were moved to different repositories outside of Dresden and later to Russia, from where the biggest part returned to Dresden in 1958. Today, we can recognize the pieces originally in the collection of Augustus the Strong thanks to their historic inventory numbers. They are treasured objects in public as well as private collections and in the art market.